Sometimes doing hard work can feel draining and hard. Whether you’re returning from vacation, uninspired by a task, or recovering from burnout, finding focus and motivation can seem out of reach during periods of change. Many of us assume that self-discipline is either something you’re born with or destined to lack, which can make the transition even more difficult. But research across psychology, neuroscience, and behavioral economics paints a different picture: self-discipline is a skill you can develop. And once developed, hard work is no longer purely draining, it can become energizing, meaningful, and even enjoyable.

This article explores the science of self-discipline and offers practical ways to:

- Make effort feel rewarding rather than draining

- Anchor in meaning when tasks feel uninspiring

- Treat setbacks as part of the growth process

- Strengthen self-control through daily practice

Hard Work Can Feel Good

Strengthening self-control through daily practice doesn’t just make discipline easier; it also changes how the brain experiences effort. With consistent practice and the right interventions, hard work can shift from feeling like it’s leaving you empty to something that fuels you.

It’s natural to think, “of course I’d rather be relaxing on a beach than studying for an exam or re-checking a financial statement for the tenth time”. Rest and enjoyment are essential parts of life. But hard work can help make those pleasures possible, and it doesn’t always need to feel exhausting. With the right approach, effort itself can carry joy and meaning.

Psychologists call this learned industriousness: the process of linking effort with reward. When people repeatedly experience effort leading to positive outcomes, the act of working hard begins to feel reinforcing. Think of cooking a meal from scratch, solving a puzzle, or finishing a run. These require focus and energy, yet the payoff for some people is invigorating rather than depleting. Research backs this up. The “IKEA Effect” tells us that some people may value objects more when they’ve built them themselves. Think of a Pax wardrobe. When you assemble it yourself, you may feel proud, accomplished and strong, even if it’s slightly imperfect. Whereas, having it assembled may leave you feeling less satisfied with the end product. Recent studies have found that the brain can be trained to treat effort as intrinsically rewarding when it consistently leads to progress.

What are practical steps to finding reward in daily responsibilities?

- Choose challenges that are demanding but achievable

- Focus on progress rather than perfection

- Reflect daily on one moment where effort paid off, even in small ways

- Observe the impact your work is having, or monitor the progress you’re making to achieve a certain goal

How to Find Meaning in Doing Hard Work

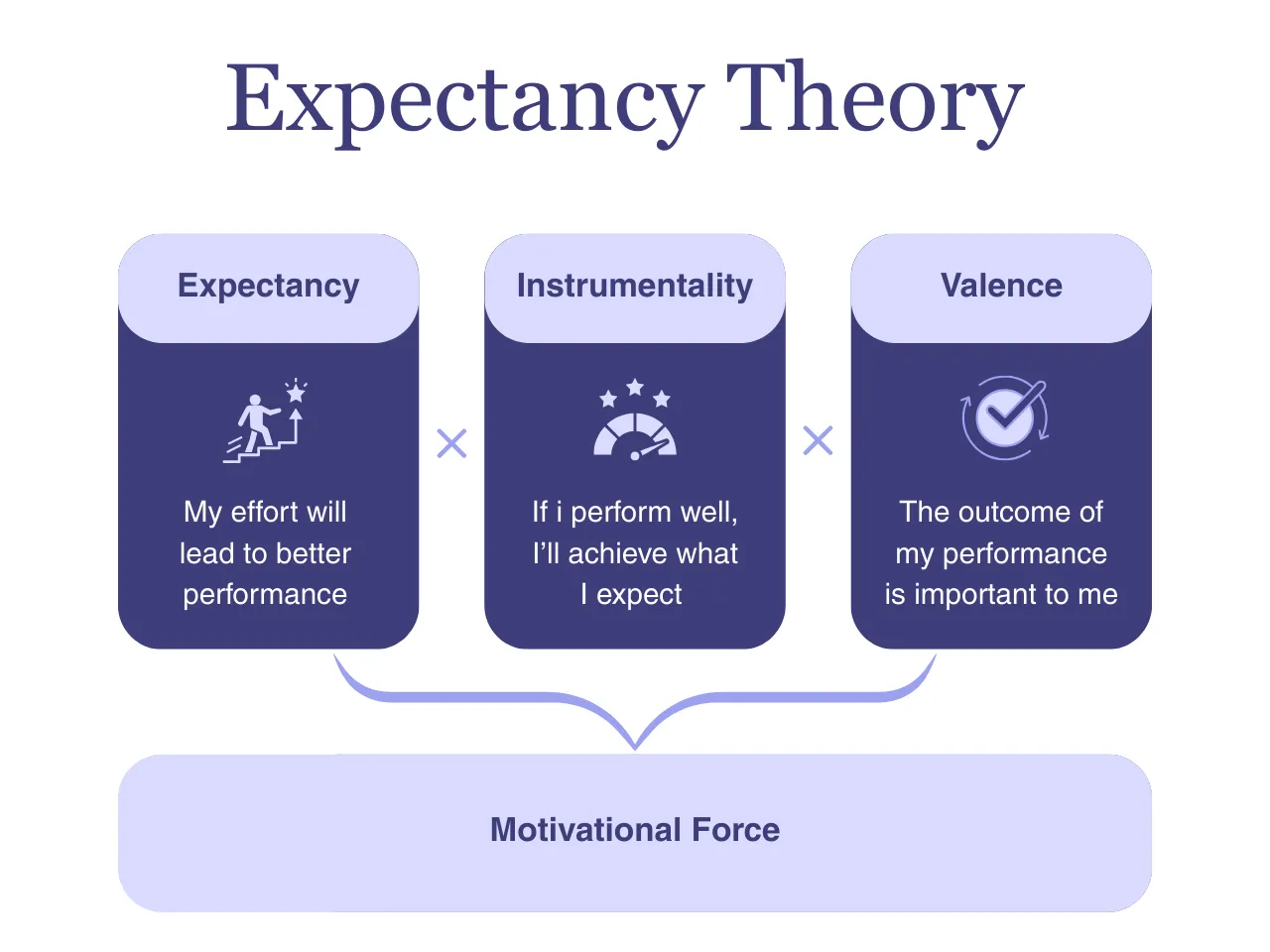

The truth is, not every task will spark joy. On days when chores or work feels tedious or uninspiring, connecting with meaning can sustain motivation. Motivation research, including expectancy theory (developed in 1964 by Victor Vroom), finds that people are more likely to persist when they are clear on why their effort matters.

Hard work is helpful for many things. It can fulfill basic psychological needs, such as the desire to feel autonomous and competent. It can also help you live a purposeful life that’s consistent with values like taking care of family or personal growth.

When meaning feels absent, research on job crafting suggests that reshaping how you work can help.

What are ways to build self-discipline when you’re feeling particularly un-motivated?

- Change the actual tasks. Would different tasks be more challenging or innately interesting to you? Could you discuss with a supervisor or teacher how to shift responsibilities or adjust the topic of your project?

- Change the people. Are there any colleagues or classmates that you enjoy working or studying with and find particularly inspiring? Could you join projects with them? Could you schedule weekly working sessions with them?

By crafting any hard task that you're doing to be more meaningful to you, you not only improve your personal experience but you may also become more productive overall.

Treating Setbacks as Growth

Everyone encounters setbacks. A project may not end as expected, or you just cannot muster the self-discipline to work or study after a vacation. These moments don’t mean failure, they’re part of the process. It means you are human, and you may need to take a break while acknowledging that you’re not proud of where things ended up.

Once you’ve taken that pause, try to re-engage your self-control. This ability to return to hard work - – whether you call it resilience, or, grit – matters even more than IQ and it can ultimately lead to greater success.

Research shows that people have better success when they focus on the process of improvement, rather than focusing only on the outcome. For example, a study by Barry J. Zimmerman and colleagues found that when people are learning darts, beginners who paid attention to each step, like how they held the dart and how they threw it, did better and felt more confident than those who only aimed for the bullseye.

Once they understood the steps, adding goals such as hitting the bullseye worked best. This shows that it’s more helpful to start with the process, the “how,” before focusing on the outcome, the “what.”

If you’re ever discouraged by the path to reaching a goal, instead of thinking about how bad it is, remember that working through each step is an expected part of the process.

Questions to ask yourself when you’re experiencing a setback:

- How can I use this setback as an opportunity to learn, adapt, and improve? Should I alter my process?

- Can I use this setback as a challenge to build my self-discipline? Should I try again? Work on a particular skill or habit?

Strengthening Your Self-Control Muscle

Self-discipline, much like a physical muscle, strengthens with consistent use. Experimental research has shown that small, deliberate acts of self-control can build stamina over time. Even seemingly minor practices, like maintaining good posture, using your non-dominant hand, or engaging in disliked tasks, enhance self-regulation for future challenges.

These small exercises recruit brain systems that link effort with reward, gradually making discipline easier to sustain.

What are some practical steps to strengthen your self-control muscle?

- Practice sitting in perfect posture every time you are at a red light.

- Dedicate ten minutes each morning to your least favorite task

- Resist the urge to check your phone the moment a notification pings. Wait five minutes before opening it

- Delay a small reward: make yourself finish a task before grabbing your coffee or snack

Each act reinforces the brain’s association between effort and positive reward, making discipline feel less like willpower alone and more like a practiced capacity. These skills not only make it easier to tackle hard things – whether at home, while studying for exams, or building a company as an entrepreneur – but also strengthen your resilience and support your mental health along the way.

Takeaway

Self-discipline is not about forcing yourself through endless hard work. It’s about teaching your brain that effort can be rewarding, rooting your work in meaning, reframing setbacks as growth, and building stamina through small, intentional practices. Over time, hard work becomes less about depletion and more about energy, resilience, and purpose.

Layla’s Takeaway Tips for Building Self-Discipline

- Link effort with reward. Choose challenges that are difficult but doable so your brain begins to associate effort with positive outcomes.

- Reflect on wins. At the end of each day, note one way your effort paid off, big or small.

- Anchor in meaning. When motivation dips, remind yourself why the hard work matters. Think about your career growth, purpose, impact, security, or personal growth goals.

- Craft your job. Adjust tasks or collaborate with inspiring colleagues to make your work more fulfilling.

- Reframe setbacks. See failures as feedback and part of the process, not as proof of weakness.

- Practice self-control daily. Small acts like posture checks, using your non-dominant hand, or tackling disliked tasks for 10 minutes have been shown to strengthen discipline over time.

- Focus on process over outcome. Sustainable motivation comes from attention to daily habits, not just end goals.

.webp)